Live Forever As A Time Worm

Or how I learned to stop worrying and hate Interstellar

Originally given as a talk at MindSwap #4, 2/7/2026.

Ever since I was young I have been obsessed with time's arrow. This is in large part because as soon as I became aware of the possibility of eternal death - around age 8, if I remember correctly - I have been consumed by both terror and the desire to outwit it. The strategies most commonly recommended to me are to "make peace with it" or "find god", but neither has proved particularly effective.

So to conquer my fear of death I long ago set out to defeat it on the only battlefield I am equipped to enter: that of the mind. I began to study philosophy in the hopes that I might come to understand the universe, and through understanding it I would cease to fear it. Without the promise of immortal life, through faith or science, I wanted to be at peace with things as they are.

Through my studies of metaphysics, two things became clear:

- Fear of death is just a matter of perspective

- Christopher Nolan's Interstellar fucking sucks

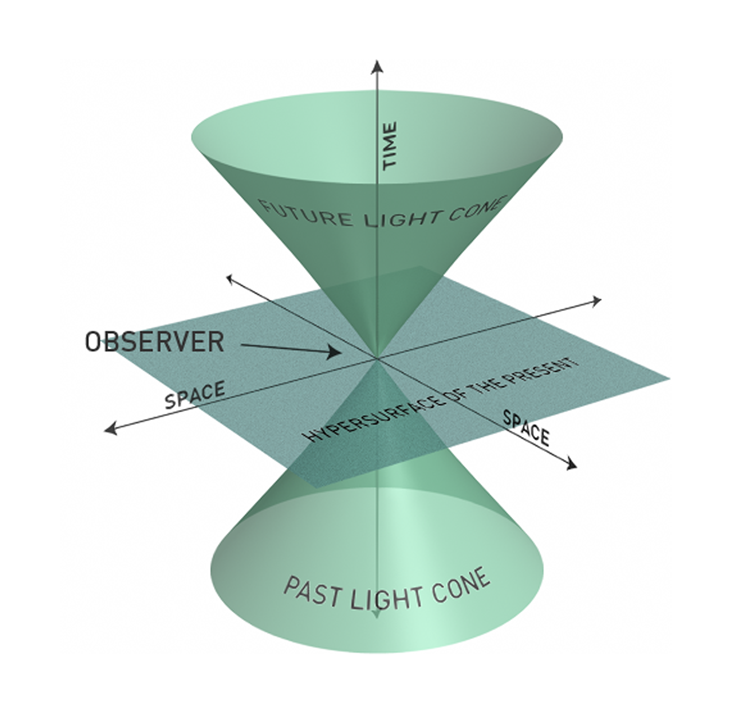

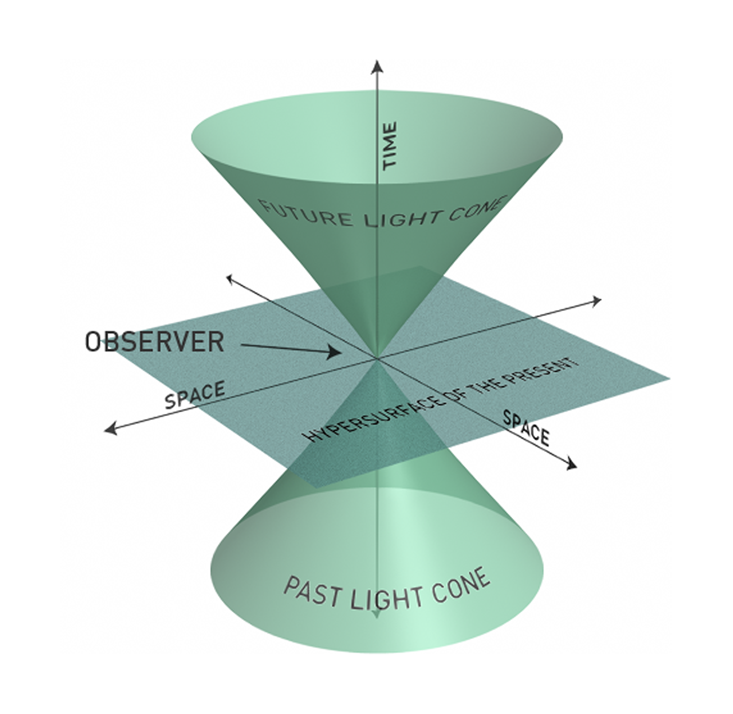

To be extraordinarily reductive about how we understand the physics of time, time is a dimension.

We are laid out across time the same way we are across space. You can think of Kurt Vonnegut's Trafalmadorians, or the "time worms" from Donnie Darko. Time, observed from a higher dimension, is visible to the Trafalmadorians like "a stretch of the Rocky Mountains" viewed from an airplane.

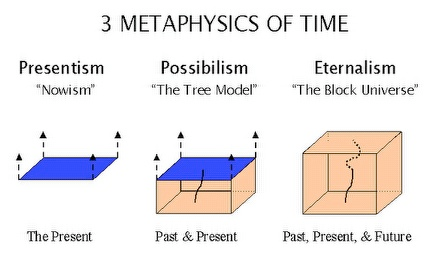

This metaphysical thesis is called four-dimensionalism or eternalism - namely, the idea that time is the fourth dimension, and we are all time worms laid out across it.

Some people disagree with this. The two major opposed schools of thought are presentism, the idea that only the present exists, and "growing block" theory, the idea that the past and present are real but the future comes into existence as it becomes the present. Growing block theory makes intuitive sense to us, but is largely disproven by relativity: "now" is not a uniform surface, since two objects moving at different speeds can't agree on what it is.

Presentism shares the same issues of not really meshing with how we understand spacetime and relativity. But more than that, I really don't like it. To me, the idea that we live in a fleeting present is surrounded only by nonexistence is both deeply sad and wildly unlikely.

Four-dimensionalism is where I found comfort. If time is a plane, we never really die. We are just laid out across part of a map that we can't see. Einstein actually put this beautifully, at the death of his friend Michele Besso: "Now he has again preceded me a little in parting from this strange world. This has no importance. the separation between past, present and future has only the importance of an admittedly tenacious illusion." He died a month later.

So, obviously, I think a lot about time, inevitability and death. And one of the ways I think all of us grapple with that is the metaphor of time travel. We go to the past to fix the present. We fight against time's arrow by changing its path.

Time travel is our favorite cultural exploration of the fight against death itself. The human dream of escaping determinism, things being other than they are. But for a four-dimensionalist, most portrayals of time travel are fundamentally wrong.

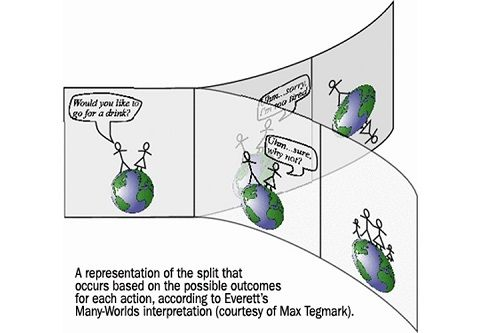

This is because, in a deterministic universe, you really only have two options:

- Nothing can ever really change - it is what it already is, or:

- Change, as we conceive of it, is laid out across an infinite number of universes, spacetime planes laid out on top of each other but never meeting. So if you were to change time, you'd really just be jumping to a different plane.. Marty McFly has not saved anyone: he's just jumping universes, leaving wreckage in his wake.

There are many sci-fi films that track with this understanding of the universe.

Arrival, based on Ted Chiang's Story Of Your Life, is often talked about as a time travel story, but it's really a story about learning to view the universe from a higher-dimensional perspective. Our protagonist doesn't change her fate or jump through time: she just eventually learns, from her alien visitors, to see the world the way the Trafalmadorians do.

But I'm not here to talk about movies I like. I'm here to talk about Interstellar. Interstellar has been widely praised as one of the most physics-accurate movies of all time. I FUCKING hate Interstellar, largely because it does not fall prey to a lot of the common misunderstandings about time but then whiffs at the finish line.

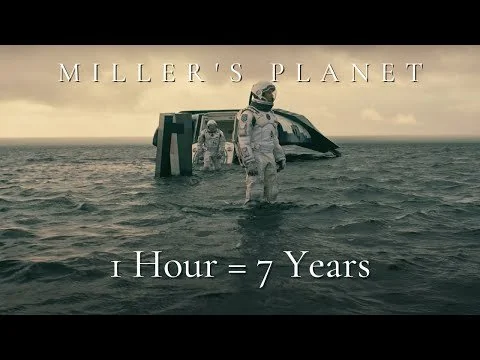

Interstellar is about an astronaut, Cooper, who is sent on a mission following mysterious alien signals to find a new home for the human race. It gets a lot of the science right, especially the ways that certain parts of the universe make time act weird, for example experiencing time dilation on Miller's Planet.

But the climax of the movie, and the point at which I became apoplectic and threatened to leave the theater, is when Cooper finally reaches the end of his odyssey, and falls into the event horizon of a black hole.

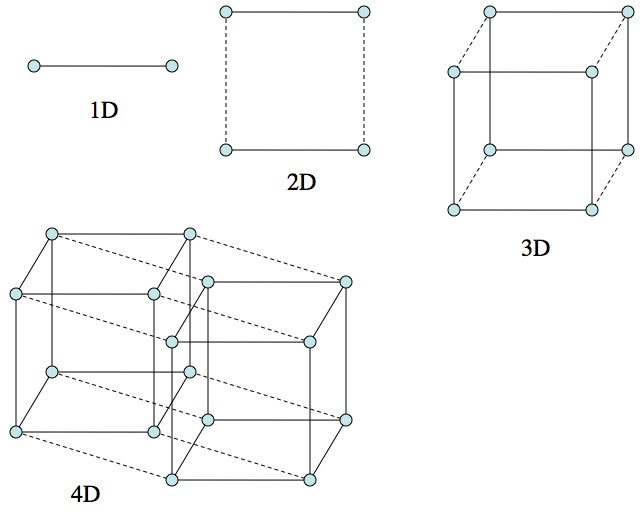

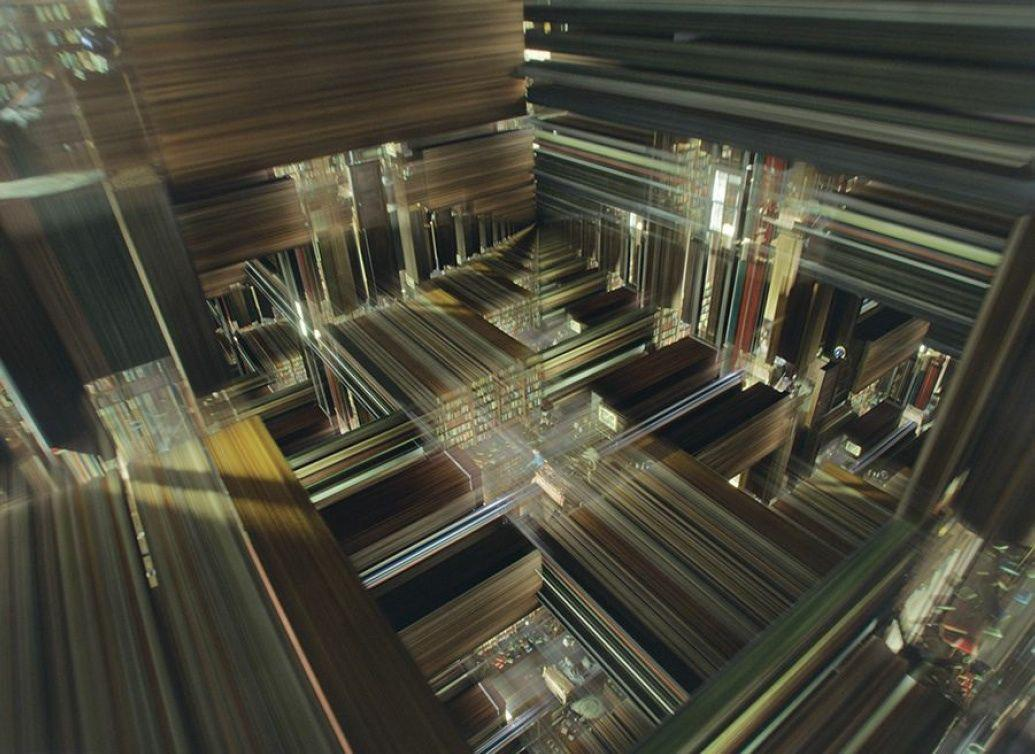

He enters a tesseract - a four-dimensional structure constructed by the aliens or advanced humans. Even this, right, is a great illustration of a four-dimensional object: it's infinite copies of his daughter's bedroom laid out across the time plane. But then he does fucking magic. He sends a signal across time to help his daughter solve for X or whatever to save humanity, and he does so with the power of love. The thesis of the film ends up being that love itself is a physical force that can transcend dimensions. It's Cooper's emotional connection to his daughter that allows him to find her in spacetime.

If you give the movie the benefit of the doubt and call what they're doing a bootstrap paradox (basically that by Cooper sending a message to his daughter he's completing a time loop that has always existed) - the emotional valence of Cooper making a "heroic choice" to change his fate, and the use of love as a supernatural force take a movie that has shown deep adherence to our understanding of physical reality and introduces the mystical and transcendental into its framework, copping out at the most pivotal moment.

And if it's not a bootstrap paradox, Cooper is simply abandoning the world in which she is going to die and jumping to one where she has better vibes.

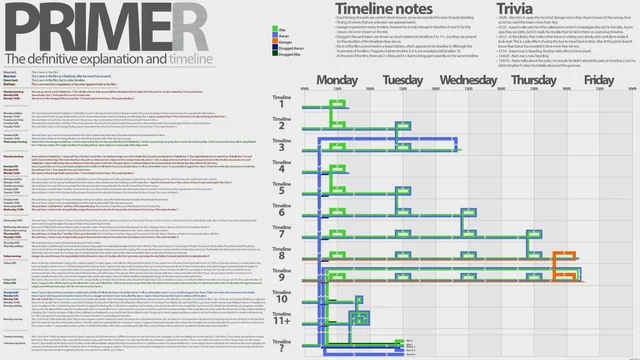

I am usually willing to forgive this type of handwaviness, but in a movie that takes such a rigid physicalist stance up to this point I find it unforgivable. And there are many, many movies that are able to get time travel right without sacrificing their emotional impact - I love Primer, which is arguably the most accurate time-travel movie ever made, but you don't have to be this incomprehensible to do a good job.

This is, obviously, a weird hill to die on. But I will die on it, because to me, it's about whether we can come to peace with dying without resorting to comfortable fictions. If we view the world through lens of linear time, then we live in constant fear of what is to come, regret what is past, crave the ability to change it. Through four-dimensionalism we can instead accept things and endeavor to see them for what they are.

Barring fluctuations in the fundamental fabric of the universe, or its eventual contraction and heat death, everything that ever has happened, or ever will happen is already laid out on the fabric of time like continents on a map. You may die, but you never stop existing, not really. And this viewpoint does not need love to behave as a magical phenomenon, or deus ex machina: it is all the more miraculous for not being so. Love is already there, and already eternal. It emerges from the substrate of spacetime, permeating our being. It is laid out across everything we are and everything we will ever be, just waiting for us to perceive it.